Fixing a Google Vulnerability

Overview

This post details the journey it took to get Google issue numbers 134447889 and 155544987 closed out and resolved.

This post focuses more on the process and political mechanics of the bug fixes, which contrasts and complements our 2020 Blackhat talk which focuses on the technical details which you can find below:

We strongly recommend watching the video before continuing.

It’s worth noting neither one of us have every worked for Google and our interactions with Google employees have been astoundingly good.

Some of the early feedback I’ve received on this post asked who the intended audience is, and what the main takeaway is?

The audience is meant to be folks on the outside looking at large tech companies wondering why and how certain security choices get made.

There is no main takeaway in the sense I’m just trying to tell that story, without imposing bias or suggesting things aught to be one way or another.

Back Story

Roughly 2 years ago I (@InsecureNature) shared an Uber ride home with Marc Newlin who in the time span of about 15 minutes detailed a way an attacker could trivially compromise GCP organizations running with default settings, default access patterns and talented engineers doing their best to follow least privilege. This conversation went something like this:

Fast forward about a month later after matter_of_cat and myself explored the platform and found the defaults were in fact as dangerous as Marc warned them to be, we began to find other privilege escalation paths that seemed at their face to be clear cut vulnerabilities.

One of these for example includes a vulnerability in Cloudbuild that allows any user of Cloudbuild to steal a credential for a Google managed service account and get access to permissions you didn’t have starting out. We detailed this vulnerability and a few more in our BsidesSF talk:

We would report these issues and to our surprise often find they would not be fixed. Since giving that talk, others have independently identified the same Cloudbuild issue, also reported it, and also seen no traction in fixing it, as seen in this Rhino security writeup

This serves as a good precursor to say, we were both familiar with what it’s like to make security changes at a large company, and at this point, has gotten a taste of the appetite and threshold required to get a major cloud provider to make changes that could break compatibility for customers.

For those unfamiliar with doing security work for a large company, the rest of this post hopefully shines some light on the internals of this process.

Filing the initial report

Amidst some of these early bug bounty filings, this takes us to issue number 134447889, Jun 3, 2019 at 9:28PM.

Here, I outlined a clear path a user with limited permissions could elevate themselves to almost full admin rights in a project. The specific example given was going from the permission dataproc.clusters.create to the project editor role. There’s an equivalent path in Dataflow and a few other API’s we pointed out too.

This vulnerability isn’t too difficult to understand, a user that can create a spark cluster, without specifying it, gets an identity with project editor assigned to that cluster. This didn’t seem right that with one permission that had nothing to do with IAM you could create a resource that had over 2000 permissions.

In combination with a few other techniques shown in the video, we became confident attackers could use these and other methods to completely compromise most GCP orgs.

Here is the rough timeline of that vulnerability report:

- June 3rd 2019 - Initial report

- June 14th 2019 - Report is triaged and recognized as a vulnerability

- July 7th 2019 - The report is changed to

Won't fix - July 15th 2019 - A commitment is made to update the documentation warning users these permissions can be abused by attackers

Normally this is the end of the story, but in this blog post, in a blameless way, I hope to detail not only what happened in that 1.5 month timeline that led to Won't fix but also how @matter_of_cat and myself ultimately in fact got the issue fixed…. sort of.

Product Management

It might be easy to point a finger at Google as if it was one entity or as if there was one decision maker and demand that entity make a change.

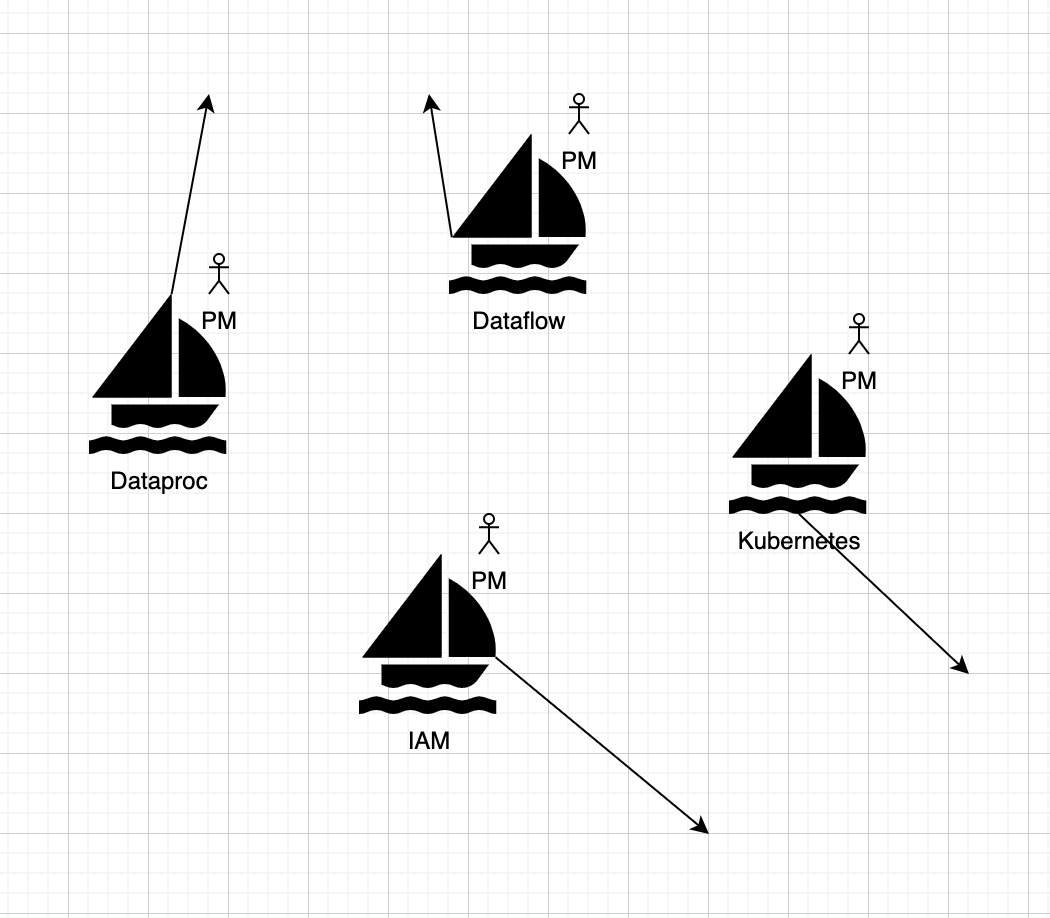

The reality is at Google, specifically in Google cloud, each product has its own project manager that is the informed captain and decision maker for that product. Their job is to constantly ask the question “Are we building the right thing?” and set the direction for the product. Below is a diagram of what that looks like:

PM’s pick a course for their product based on customer feedback, and customer data. A product that’s widely adopted and liked, makes for a successful PM.

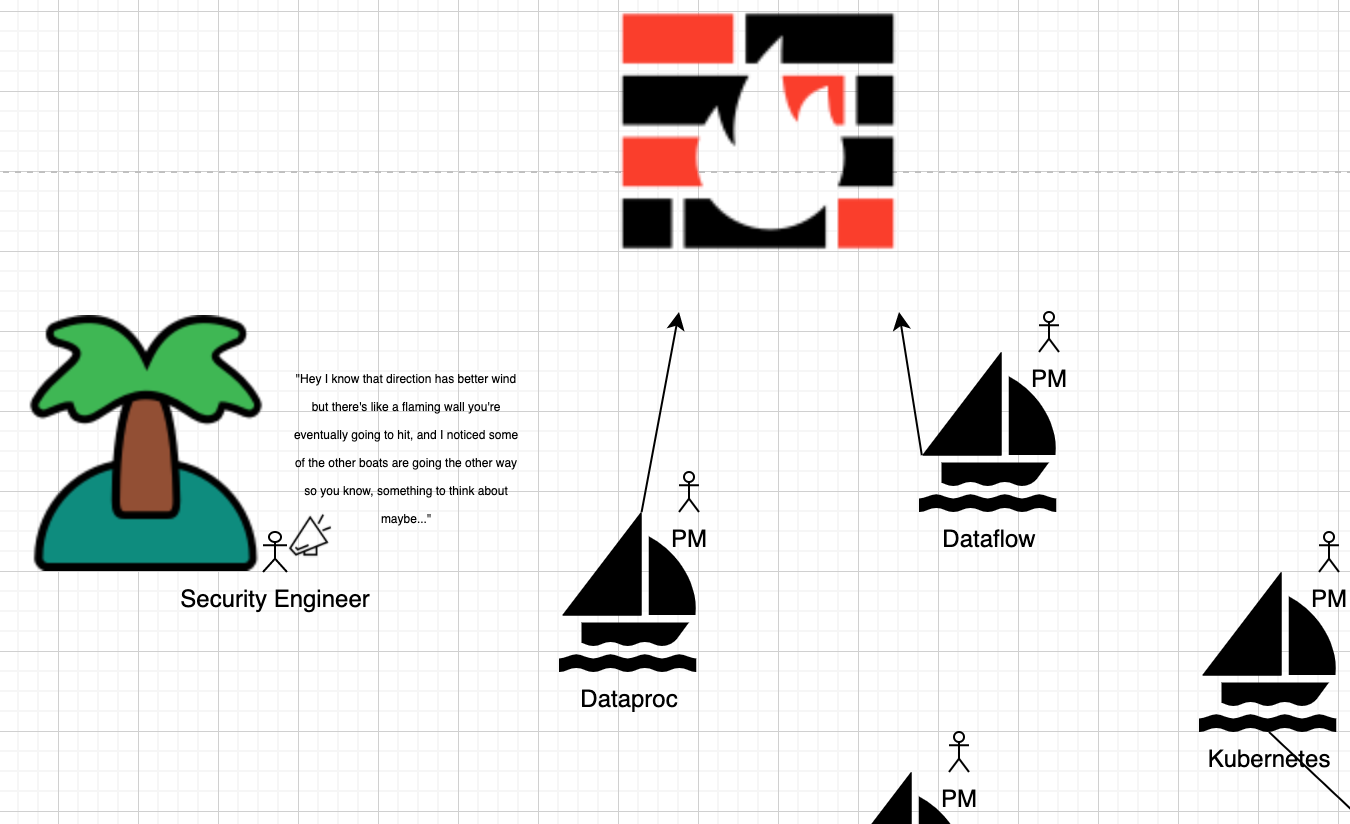

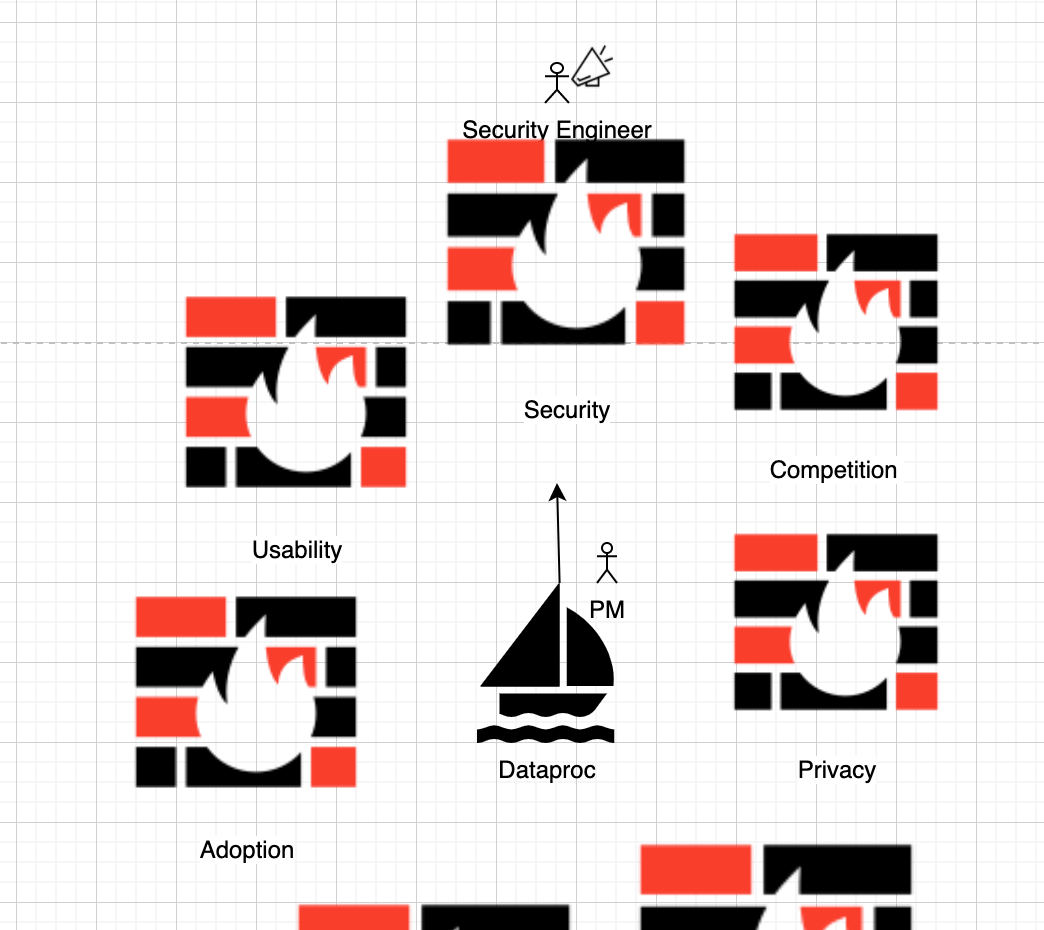

You might wonder how security plays into this picture. Generally speaking, security sits on the sidelines consulting PM’s and offering input based on known risks, allowing PM’s to make more informed decisions. I’ve illustrated this to the best of my ability in the diagram below:

Of course the reality is likely more complicated than that, so doing my best to account for my own biases here’s a revised version:

So all that being said, here’s how I expect the conversation played out between June 14th and July 7th of 2019:

Security Engineer:

“Hey, I noticed your API allows users to make use of the default service account without explicit permissions to use is. The IAM team typically recommends the user has actAs over the service account that gets assigned to the resource they spin up”

PM of Dataproc:

“Oh yeah, we actually know about this. It’s a legacy issue that’s been around a long time. The issue is all of our users don’t use that permission today, so it would break everything. Plus the actAs workflow has been shown to add friction to adopting new API’s, and we’re really trying to make Dataproc as accessible and low friction as possible”

Security Engineer:

“Okay. I understand where you’re coming from. The IAM team is trying to get everyone on the same page about this though, this pattern could repeat other places if we don’t fix it”

PM of Dataproc:

“I understand where you’re coming from, I think we’re going to need a better solution from the IAM team though”

Security Engineer:

“Okay what should I tell the researcher that found it?”

PM of Dataproc:

“We’ll set this one to won’t fix. Let’s update the documentation so we don’t get more submissions like this in the future, and I’ll make a note to chat with the IAM PM about a more long term fix”

Note, everyone in this conversation is doing exactly what they should be doing organizationally. The PM is trying to make their product as successful as possible, and the security engineer is articulating risk with the chosen path.

Organizationally security doesn’t sit over product and dictate to them how things must be. There are some companies that take that heavy handed approach, and it comes with its own sets of drawbacks. Usually companies that give security more authority end up with trust issues, as the incentives shift from making informed choices, to simply leaving security out of the conversation so they don’t add a list of demands.

So we end up with a product manager that’s success is measured on their product not failing, and a security engineer saying the only way to prevent this issue, is to risk the health of the product.

The issue gets risk accepted.

The “Bigger Picture”

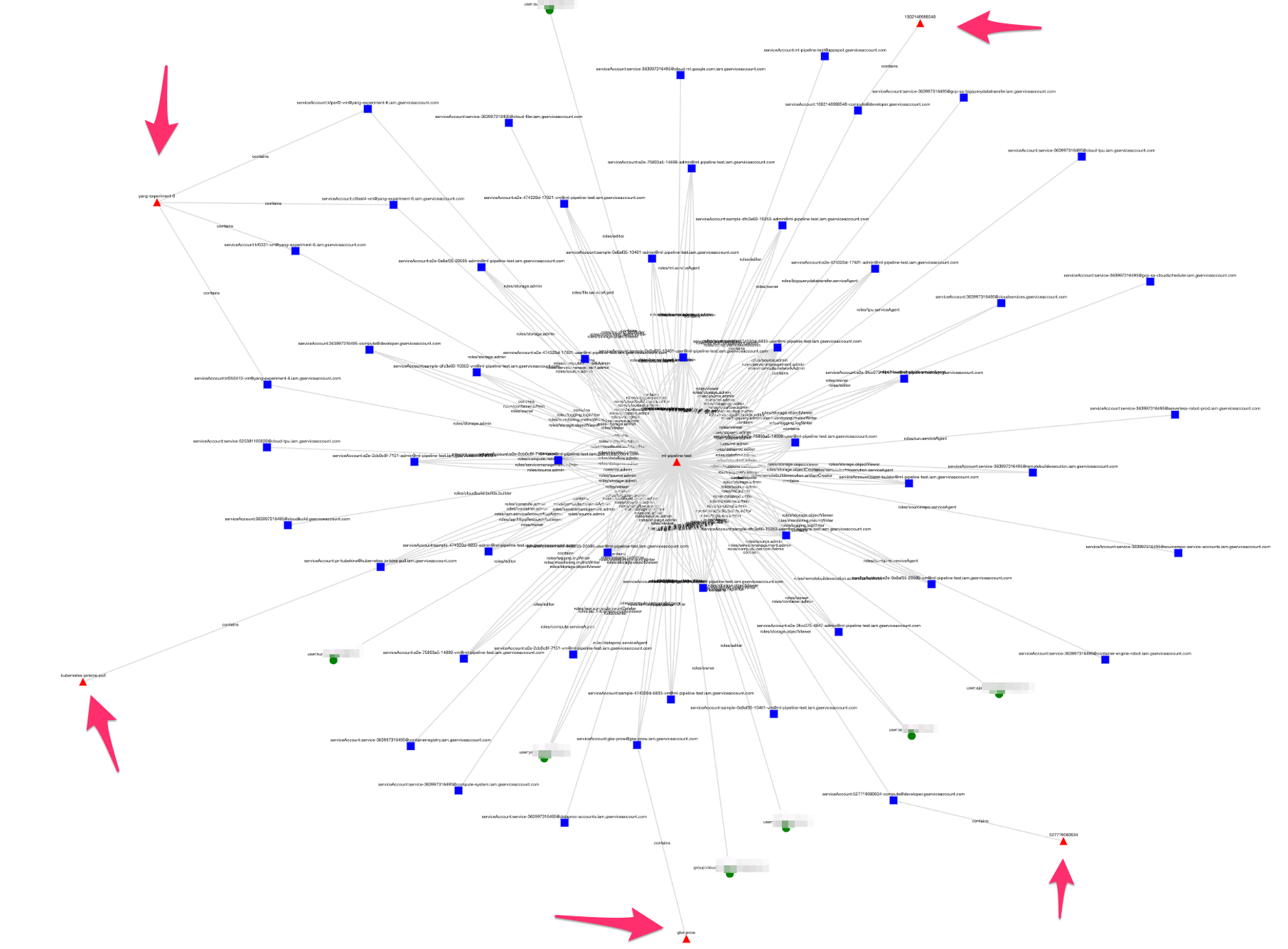

As mentioned earlier, the above issues combined with a few other techniques lead to what we believe is a clear path to compromise any GCP org. Some time after the initial report, matter_of_cat and myself had began to collect a list of permissions that could privilege escalate to other roles. We also began to study access patterns across multiple projects. We made graphs showing how interconnected these projects typically are in a real world setting, and we showed how those roles that bridged projects could often be used to take full control of the foreign project via the permissions we found.

We went over this in great detail in our Blackhat video, but one piece we left off of the video, is we actually were able to find a number of IAM documents on the internet detailing the IAM of projects internal to the Google.com organization. These projects are used by Google internally and aren’t meant to be public. Naturally, we graphed them. Here’s an example of one below:

This graph shows identities that have role bindings to this central project ml pipeline test. We can’t see any of the role bindings going to any other projects, but this one gives us a story. We can see service accounts created in other projects (where the arrows are pointing) that have role bindings into this project. 4 of these roles could privilege escalate to project Owner. These are the same access patterns we identified in every other organization we looked at.

To us this cemented what we already knew: almost every sufficiently large organization in GCP could be attacked the way we outlined in our video, which includes Google themselves.

We were stubborn to see progress on these issues, even when traditional vulnerability disclosure pipelines didn’t yield results. We saw this as an opportunity to educate folks on the larger concert of issues, which in isolation can be written off here or there, but in summation we felt couldn’t be ignored.

Nepotism in Tech

At this point, we did what any obnoxious security engineer would do, I pinged my friends at Google asking for direct facetime with the PM’s. Soon we got put on email threads with PM’s where I was exchanging graphs with them, and these eventually lead to in person meetings.

This felt great, and gave me a much better understanding of how products get built. PM’s take input from customers, and from security engineers internally, so in this rare opportunity, I could act like a customer, but have the asks of a security engineer.

I remember very specifically going into a Google office, sitting down with them, and explaining everything on a whiteboard. They were professional, and great to work with.

In my experience a Google PM is very “new feature” development focused. So if you could fix an issue with a new feature, we could make progress, but typically suggesting breaking backwards compatibility on an existing feature went nowhere.

One new feature included enhanced queryability in asset inventory to shine better visibility org wide on these cross project bindings. Another included an org policy that disabled automatic default Editor role grants.

These tools helped for an organization that has security from day one, and the ability to configure defaults and setup alerts for dangerous behavior, but this wasn’t going to help too much for all the organizations that couldn’t afford those kinds of security resources, or those that had built up too much tech debt around the way things were working.

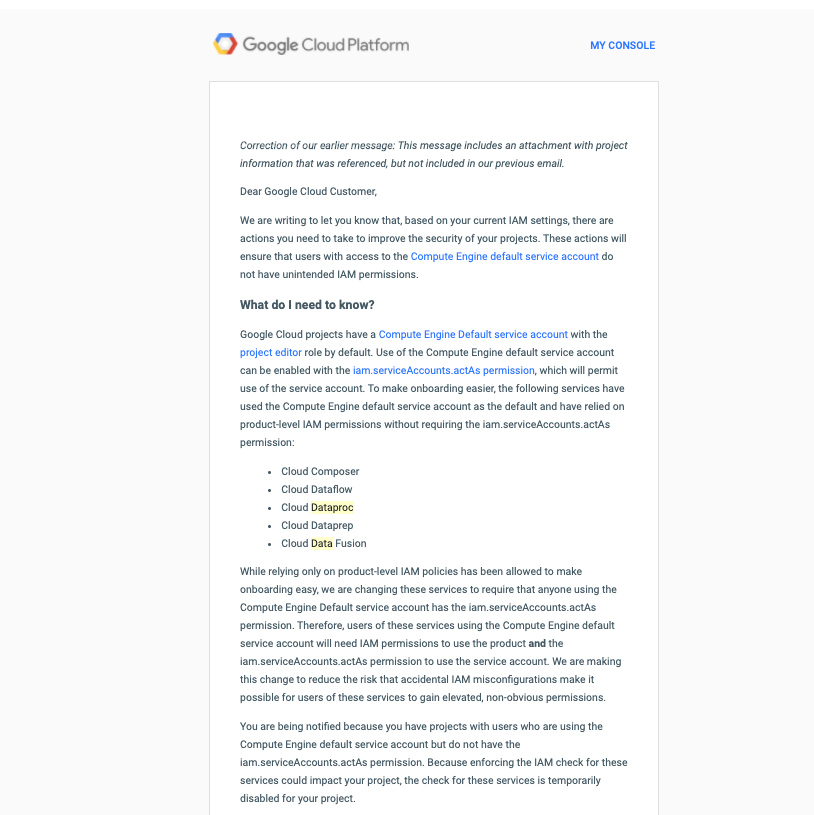

On top of that, our privilege escalation issue remained in Dataproc, and the following additional list of API’s:

- Cloud Composer

- Cloud Dataflow

- Cloud Dataprep

- Cloud Data Fusion

Public disclosure

At this point we felt like we had taken things as far as we could. We hit a wall disclosing through the bug bounty, and we made as much progress as we could working with PM’s to ship new helpful features.

So we submitted to Blackhat and Defcon. Both were accepted, and we gave Google 90 days notice that the talk was coming. This disclosure included a full writeup of all issues, as well as internal Google diagrams showing they were vulnerable. This was issue number 155544987.

To our surprise, this spurred significant action and dialog, which went further than we were able to go on our own.

Here’s a quote from a security engineer following that submission:

“I also ended up having to do a lot of philosophical discussions around the meaning of permissions and obligations and how to define what should and shouldn’t be treated as vulnerabilities. In a way, you forced our team to read philosophy research papers on deontic logic and have discussions about it.”

This highlights one of the main themes I hope people take away from this writeup. Security vulnerabilities are often not binary; they’re conversations and trade-offs. A bug bounty forces you to distill every finding down to a binary “this should be paid” or “this shouldn’t be paid” but the reality is much more complicated.

Everyone, PM’s and Security Engineers, are all doing their job to the best of their ability, and sometimes bluntly put, these jobs can conflict with one another, and a vulnerability gets turned into a negotiation and compromise.

That being said, every once and a while, someone with a lot of influence high up in the organization takes notice and forms an opinion. That is what happened when we gave our 90 day notice.

PM’s and Security Engineers all of a sudden came into perfect alignment and the following email got sent out to all customers using the above API’s

One year after we reported the issue, many emails and in person meetings with Google PM’s and Security Engineers later, and one impending public disclosure, we were able to get this specific issue fixed.

It’s worth noting the Cloudbuild issue, and other privescs we and others have talked about have not been resolved.

Conclusion

My hope is that this writeup gives folks a little sneak peak into how security works internally at a major cloud provider, or just a large tech company in general.

I think everyone we worked with acted professionally and were great to work with, and I personally want to thank everyone who took the time to meet with us.